All Roads Out Of Jackson Hole Lead To This Week’s Jobs Report

Federal Reserve Chair Powell accomplished his objective at the virtual Jackson Hole conference last week. Especially after Powell mentioned slack in the labor market, the jobs report will be crucial this week. The negative impacts of the rising infections are being felt in some data.

GLENVIEW TRUST’S BILL STONE ON CNBC DISCUSSING MARKETS, FED POLICY, AND THE ECONOMIC IMPACT OF INFECTIONS

Markets Eyeing The Fed And Covid Damage

Markets Eyeing The Fed And Covid Damage

Just as Bob Dylan sang, “you don’t need to be a weatherman to know which way the wind blows,” short-term Federal Reserve policy has suddenly become easier to predict. The negative economic impacts of the increase in the Delta variant infections are beginning to be felt.

Berkshire Hathaway’s Portfolio Moves In The Second Quarter

Berkshire Hathaway’s Portfolio Moves In The Second Quarter

Berkshire’s $293 billion investment portfolio now consists of 44 companies and is very concentrated, with the top 5 holdings accounting for over 76% of the total portfolio. There were no new purchases, but Berkshire added to significant stakes in two companies.

A Week Of Retail Therapy For The Markets

What To Watch In Inflation And Berkshire Hathaway’s Earnings

What To Watch In Inflation And Berkshire Hathaway’s Earnings

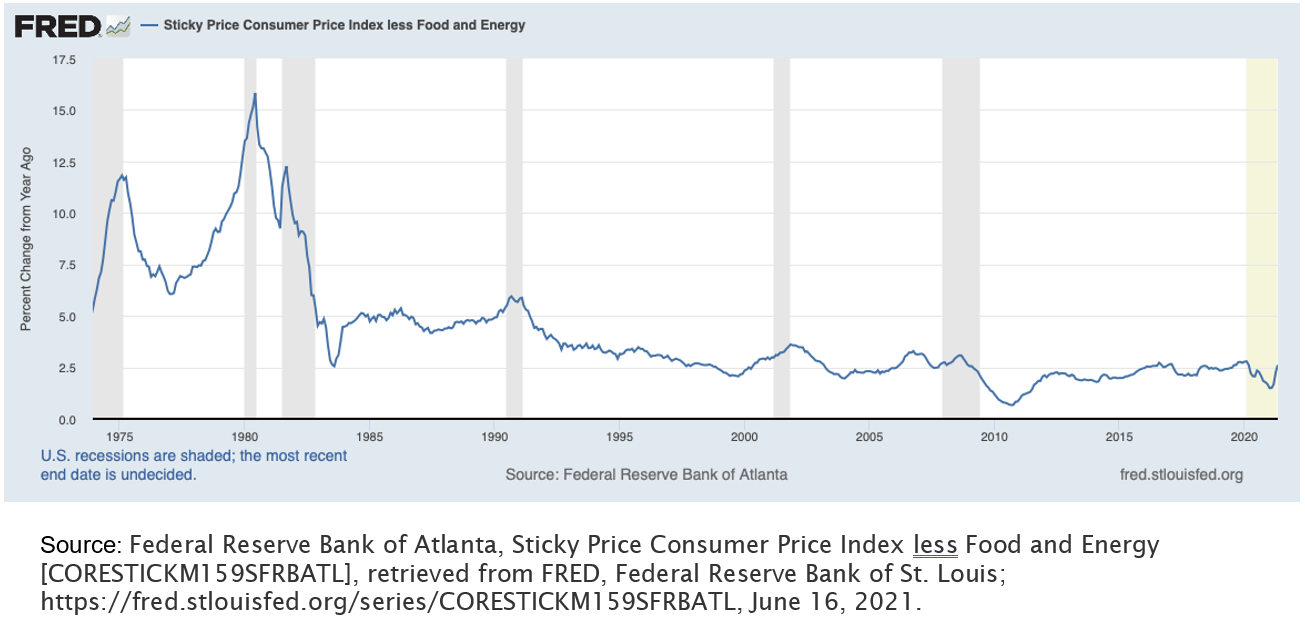

The highlight of a thin slate of releases this week will be the July consumer inflation (CPI) readings. Berkshire Hathaway reported earnings on Saturday and are worth reading because it can provide a broad look at the economic rebound from COVID-19 due to its many operating businesses.