Lessons From The Masters In Omaha

I began attending the Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting in Omaha in the mid-2000s and continued to travel there despite it starting to be broadcast online a few years ago. Unfortunately, the Covid outbreak interrupted my yearly pilgrimage to Omaha for the last two years when the meeting was entirely virtual. As I prepare to head to the “Woodstock for Capitalists” on April 30th, it seemed an optimal time to revisit some timeless lessons from Warren Buffett, CEO and Chairman, and Charlie Munger, Vice Chairman.

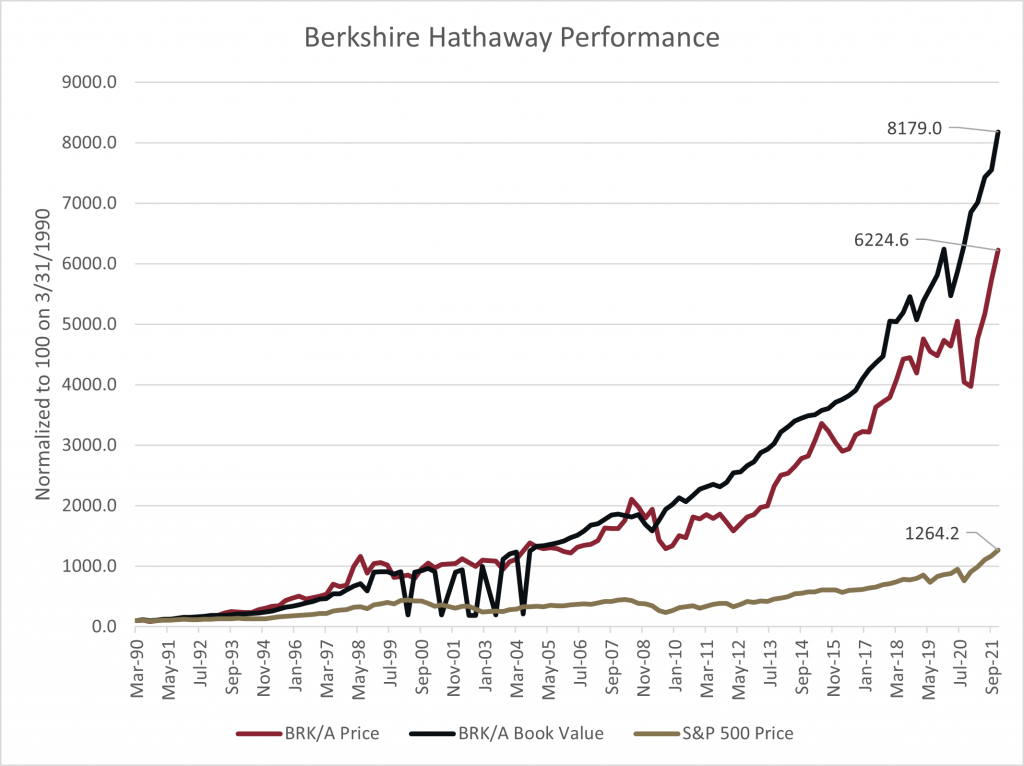

While Buffett and Munger likely need no introduction, their partnership in managing Berkshire has produced arguably the most remarkable extended performance for investors ever recorded. Since they began operating Berkshire in 1965, the stock has risen at an annualized pace of 20.1%. The S&P 500 has had an annualized return of 10.5% during the same timeframe. Even over a shorter period, Berkshire has significantly outperformed the S&P 500 (Chart 1). As a rough proxy for the growth of the company’s intrinsic value, the book value growth has also far outstripped the appreciation of the S&P 500.

Source: Glenview Trust, Bloomberg

Chart 1 – Berkshire Hathaway Performance

While there are countless lessons to learn from Buffett and Munger, this piece will distill their wisdom into four timeless insights.

Invert, always invert. – Charlie Munger

Munger made a case for using inversion for difficult investment questions. Munger borrowed this idea from the 1800s German mathematician Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi. He believed that the solution to many vexing problems in mathematics could be solved if inverted. This inversion idea is just one of the mental models that Munger uses to make better decisions, but it is arguably one of the most powerful.

An example of applying this maxim could be how to select the best investment manager. So instead of focusing on what works, one could consider what does not work and avoid it. Empirical evidence has shown that using three-year manager performance in the traditional manner to make diligence decisions leads to underperformance. Interestingly many institutional and individual investors still use a manager’s three-year outperformance to hire or underperformance to fire a manager as an integral part of their due diligence process.

While not all insights from using inversion result in a contrarian outcome, the facts surrounding manager selection lead to one. Investors should either ignore the short-term relative performance of a manager or even favor managers with recent underperformance as part of a robust manager selection process.

We never want to count on the kindness of strangers in order to meet tomorrow’s obligations. When forced to choose, I will not trade even a night’s sleep for the chance of extra profits. – Warren Buffett

In addition to their investment results, one thing that stands out with Buffett and Munger is their ability to produce such great returns over such a long period. The investment business is littered with shooting stars that had great returns only to flame out, sometimes in spectacular fashion. Risk management continues to be a hallmark of the Berkshire model. Buffett famously pledges to keep at least $30 billion in cash on Berkshire’s balance sheet to never worry about meeting obligations. For example, Berkshire had about $144 billion in cash on hand at the end of 2021, with the vast majority in U.S. Treasuries. During extreme market turmoil like the Global Financial Crisis, others can rightly become worried about the safety and liquidity of even short-term bond holdings. Buffett chooses not to take the extra risk with the cash position to earn more yield, so he has the dry powder to make acquisitions, and counterparties can rely on Berkshire to complete any agreed-upon transaction. This stance has allowed Berkshire to make some investments during severe market stresses, which has added to the long-term track record and lowered the risk of ruin.

Time is the friend of a wonderful business, the enemy of the mediocre. – Warren Buffett

While Buffett began his investing career buying “cigar butts,” low-quality but cheap companies with one more “puff” left in them, he evolved to focus on higher-quality companies with Munger’s influence. Buffett now says that “it’s far better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price.” Valuation still matters; as Munger notes, “in our way of thinking, all intelligent investment is value investment.” Some of Buffett’s largest and most successful investments, like Coca-Cola (KO) and Apple (AAPL) have clearly fit this mold.

These are not just empty words because an innovative analysis of the source of Berkshire’s investment performance showed that Buffett’s “focus on cheap, safe, quality stocks” was a primary driver of his outperformance. Returns were also boosted by Buffett’s decision to structure Berkshire Hathaway as an insurance company. The two most essential concepts in insurance investing are “float” and underwriting profit. An underwriting profit means that the insurance premium exceeds all insurance claims and expenses. In simple terms, the float is created for insurance companies because insurance premiums are paid before any claims are made by the insured. Before insurance losses are reimbursed, insurance companies like Berkshire can invest the float, sometimes for years. Berkshire has a history, unlike many insurance companies, of earning an underwriting profit, meaning that their float costs them nothing and makes them money in addition to allowing them to earn a profit off of investing the float.

If you own your stocks as an investment – just like you’d own an apartment, house, or a farm – look at them as a business. – Warren Buffett

Benjamin Graham, Buffett’s mentor, taught him much about value investing, but one of the essential truths was to analyze stocks as a business and not react to short-term fluctuation in the quoted price of a stock. Buffett has said that chapters eight and twenty of Benjamin Graham’s “The Intelligent Investor” book are the bedrock of his investment process.

Graham thought investors should look at stock holdings as owning a part of various businesses, like being a “silent partner” in a private company. Hence, stocks should be valued as a portion of the company’s intrinsic value, not as something that has a constantly changing price on the stock market. An investor should take advantage of the stock market’s fickle view of a company rather than allowing it to dictate what one should do. Valuing stocks as a business and purchasing stock with a “margin of safety” enable investors to ignore the market’s vicissitudes. For Graham, the “margin of safety” meant buying at a price below the “indicated or appraised value,” which should allow an investment to provide a reasonable return even if there are errors in the analysis.

In addition to the timing around the Berkshire Hathaway meeting, the recent turmoil in the markets made it an optimal time to revisit investment first principles. Given the growing downside risk to the economy and the current inflationary environment, our view is that investors should focus on quality and dividend growth plus companies with pricing power when searching for opportunities during this selloff. Quality is defined as high returns on capital, consistent earnings, and low debt levels, which should help the company deal with any economic slowdown. As always, investors should work with their Glenview team to ensure their asset allocation provides the financial means to persist through any volatility.

Following the Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting, further dispatches from Omaha will be posted to The Glenview Trust website if you are interested in reading more.

Please do not hesitate to contact your Glenview team or me if you have any questions.